There is a great contradiction in what it means to be both an introvert and an artist. I have no doubt there’s been much written about this and I’m sure I would benefit from seeking those writings out; however, being someone who struggles with it, and with trying not to see it as a contradiction, I’ve found there’s much that can be said about it.

Over the past couple of years, I’ve changed profoundly as a writer. Part of this is the fundamental growth that comes with passing time: none of us is the same person we were a year ago, a month ago, even a day ago. And another part—the more active part—of my own growth as a writer is almost obsessively willful. I’ve been inconsistent with this blog, and will probably remain inconsistent because I don’t know what to say. In fact, it’s more than not knowing what to say, it’s the struggle of feeling whether I should be saying anything at all, and if I should, then how should I say it? This internal conflict mirrors the struggle of any artist when it comes to their own art, but in a much smaller way because, at least in this context, I’m talking about a blog that I’m not even sure anyone reads. So I decided that this is what I wanted to talk about, because I think talking about the creative process is both fun and incredibly interesting, in part because the creative process is such a depthless mystery for each one of us. And talking about things, or writing about them (especially that, for me), is both cathartic and insightful. It helps me process and understand things more, and there’s so much I can say about my growth as a writer—and hopefully provide some helpful insight or something of that sort, for someone reading this, about their own processes, or their own art.

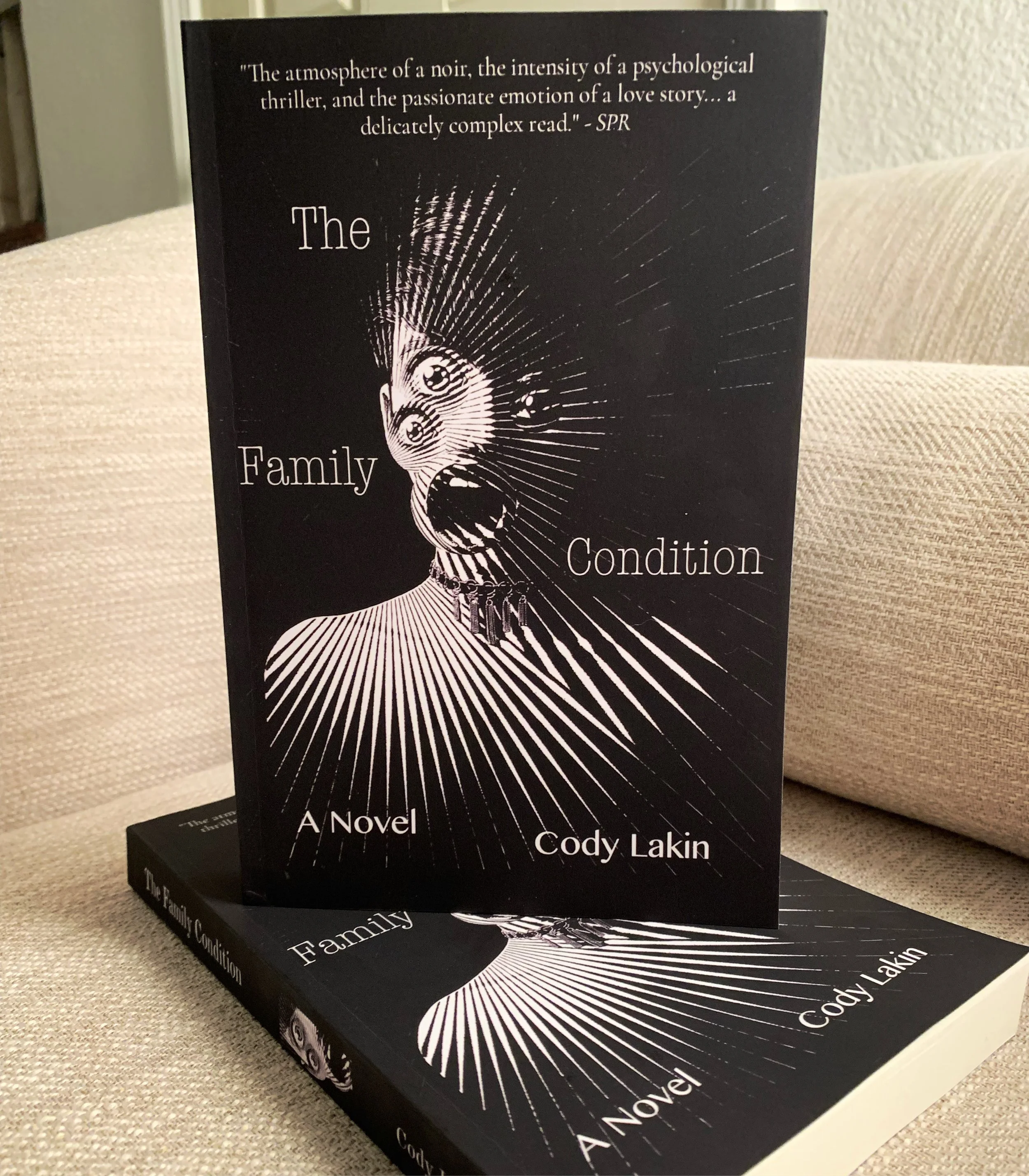

To date I have three novels published under a small traditional press called Black Rose Writing. My first, OTHER ENDINGS, is a bizarre and emotional ghost story that I look back on and try not to cringe about. The second, FAIRLANE ROAD, is a dark urban fantasy thriller with a heavier focus on philosophy than on plot, with interesting characters and an exciting story. My third, THE GIRL WITH A FAIRY’S HEART, delves deeper into the world alluded to in FAIRLANE ROAD, and which I still regard as a truly strange book, but which I’m still fond of. I have a complicated relationship with each of these books on their own, and even more so on a broader scale when I look at them all at once. For most of my life I’ve simply blazed forward with my writing, story after story, the creativity flowing and bursting out as if of its own accord. And it’s produced some fun, odd things.

And things have changed so much since those books, even since my writing of the third book, which was released just last year.

At the end of 2018, I finished a book that was unlike anything I’d ever written before. It embodied themes I’d been wanting to explore for a long time, and seemed to be the kind of story I wanted to write going forward. I was excited and nervous and uncertain about it, especially because, for the first time, it was a very personal story. It’s called WHEN TIME WAS KIND TO YOU, and it’s the book that helped me cut through much of the other kinds of writing I’d done in the past. It opened the doors of the revision process to me, teaching me how to do it more productively and extensively. I did roughly six or seven drafts of it, approaching every read-through from a different angle, smoothing it out and tweaking it, erasing or replacing scenes and entire segments. It was such a process.

And what I’ve had to come to terms with recently is that I’m no longer in love with it—which is a new record. It usually takes me awhile longer to look at one of my stories in a new light, or to feel that I’ve outgrown it. This happened with WHEN TIME WAS KIND TO YOU within a few months. It’s an important book in my development, perhaps to date the most important, but it’s one I will likely leave behind and maybe, one day, revisit and rewrite from scratch.

My writing of that book straddled a line in my development as a writer. Partway through that book, I began to seek out ways to educate myself in the craft of storytelling in ways I never had before, and this opened up doors into my creativity and growth as a writer—and person—that I had never even known were there. I devoured lectures on writing (there are quite a few different kinds that can be found for free on YouTube, practically amounting to free college classes) and devoured them again and again, absorbing everything I could. I’ve done this with narrative storytelling and literature, and have done so with similar lectures on screenwriting and storytelling in film, realizing that there’s as much to be learned from the world of cinema as there is from literature. In fact, the crossroads where they meet is an incredibly interesting one. Where screenwriting requires immense efficiency, novel writing has much more room and space for experimentation and tangents of various kinds, and I think there’s a middle ground that great writers have found.

This education process has given me a clearer view of my own writing than I’ve ever had. For example, I’m a pantser, or a gardener, in the sense that I don’t outline my stories and then write them, I simply write them “by the seat of my pants.” It’s always been this way and will likely always be this way, unless I decide to write an intricate mystery one day. However, I’ve learned to retroactively outline my stories, or at least break down the components in order to get a clearer view of my work, which will aid me immensely in the revision process.

The difference here, between the kind of writer I used to be—even just a year ago—and the kind of writer I am now, boils down to intention. In the book I’m currently working on and almost done with, there is a clearer, more focused intention behind the story’s components, behind the story’s tensions. There is a clarity to how the characters contrast each other, to how each of them grows across the story, and it is so exciting and so exhilarating. This is especially the case when I realized how important it is to be mean to your characters.

I decided I wanted never to stop growing as an artist and as a person, whatever that means. The path to success as an artist has much more to do with discipline and persistence than it does raw talent—although that is, of course, fundamentally important—and, for the first time, I’ve begun to feel confident about that. And it is an incredible, hungry feeling, to keep striving, to keep going, to never allow myself satisfaction in this.

But there remains the problem of deep introversion in the world of art. I’m not good at marketing myself, I’m terrible at selling my own books, not only because quality matters to me and I know I have grown so much since my published books, but because it’s deeply hard for me to feel okay about going up to someone and basically saying “Hey, I’m an author and I have some published books. You should read them.” I’m basically my own worst enemy in this scenario, and it’s ironic because I’m literally a bookseller and have the opportunity to sell my own books at the bookstore I work at. Which leaves me emotionally conflicted and nervous and wondering, “What the hell is wrong with me?”

I know that self-doubt is a fundamental part of being an artist, and I believe that goes for every artist. The battle against resistance—the “War of Art,” which happens to be the title of an excellent book I recommend to anyone, especially any artist who struggles with resistance—is rooted in the mere act of creating art. It is the upward climb of creating honestly and truly and effectively, and it is equally the climb of knowing you have something to say, and then getting past the resistance of feeling that you have a right to say it, and then getting past the resistance of knowing how to say it, and then getting past the resistance of finally fucking saying it—and saying it again, and again, and again.

In a past blog post I talked about struggling with impostor syndrome. This is something I do struggle with and feel, but, more recently, I realized—and have been processing, through a great deal of resistance and anguish—that I attributed far too many fundamental things about myself and my own mind to impostor syndrome than makes sense. I could go on about that, about coming to understand depression, and then realizing I don’t understand it at all, and trying to come to terms that it is, in fact, something I struggle with and have struggled with for long, long time, in far more acute ways recently than in the past, but for now I think this is all that needs to be said.

These are things I struggle with, these things are part of the climb of creativity and art for me. They won’t be for everyone, as we all have our own struggles, obstacles, resistances.

One of the most important things I realized, somewhat recently, is this:

I used to think that, were I to become a successful enough writer to support myself as a full-time writer, I would adjust my writing schedule to be much more disciplined. I used to think there was some line I needed to cross, some validation I needed to receive, in order to become the kind of writer I someday wanted to be. And I used to fall into the trap that life was in the way of art, like having to go to work.

I don’t think that way anymore. I genuinely feel my life has changed since coming to this realization.

I decided to write as if I were already a successful writer, and the result is that I’m more productive than i’ve ever been. For a few weeks, recently, I was writing 2,000 words a day, striving for that word count because that’s the number Stephen King names in his book “On Writing.” I didn’t always reach 2,000 words, but I was always close enough to feel content, and the striving was more important than the actual quota. This was interrupted by an intense, unrelated drop into depression, but I’ve been working back towards that and coming up strong. I set time aside every day, sometimes in short bursts, to write, and some days it comes smoothly, other days it’s like pulling teeth out—to borrow a metaphor I’ve heard a few times. I’ve learned it’s more important to get it written instead of getting it right, which is all the more comforting because of my refined revision process. You can’t revise and improve what isn’t written at all. So get it written.

I decided to stop valuing the wrong opinions, to stop looking at art any way aside from how I chose to look at it, and this has brought me peace. Everyone has their opinion, everyone has their influence—positive or negative—and everyone, most important, has their own process. There is no “This should be done this way,” or “This is how art is,” there is only the individual’s opinion and personal process, each as valid as the other. What is true of one person’s creative process—or even life, for that matter—won’t necessarily be true of yours. Sometimes one person’s can even be toxic to yours. Sometimes inspiring.

And I’ve learned that life and art aren’t ever in the way of each other. If I could become a full-time writer, I’d absolutely make adjustments in my life, but I wouldn’t quit my job, wouldn’t turn into a different person or drop off the face of the world. On the contrary, I value the various aspects of my life in how they feed each other and enrich each other, especially the work, the grind, the hard parts, even when those parts feel impossible to trudge through or threaten to drive me mad.

That’s life.

That’s art, too.

In his essay “The Myth of Sisyphus,” Albert Camus illustrates a profound point about life using the Greek myth of Sisyphus, who was punished by the gods to push a giant boulder up a mountain. Whenever he finally reached the top, the boulder was doomed to roll back down to the bottom, and Sisyphus was doomed to return back down the mountain in order to push it back to the top. Over and over in eternity. But the idea is to imagine Sisyphus happy. The struggle isn’t something to be overcome in our relationships, in our art, in our lives. It’s something to revere. Work doesn’t have to be done with the goal of finishing, otherwise the work becomes torture on the way to the end.

Camus said it best.

“The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”