As a kid, I grew up watching the Los Angeles Lakers. Nowadays I don’t really watch sports except when I’m with family, but I have all kinds of wonderful memories of watching the Lakers. Big family parties with my uncles and cousins and parents in southern California, with the whole house erupting in cheers of triumph or frustration. A big part of the draw, for me, was watching Kobe Bryant, who seemed to come out with something amazing every single time he played.

I say all this not to go on a long tangent or anything, but because I once saw a clip of Kobe talking about confidence. He was known for what he called his “Mamba mentality,” a philosophy of immense discipline and dedication. What he said about confidence has stuck with me.

“Confidence is preparation.” He said it in so many words, but that’s what it came down to. If, in practice, you practice a shot hundreds or even thousands of times, when it comes to the actual game, there’s no need to doubt yourself. You’re just doing what you’ve worked hard practicing over and over; it may even come as second nature.

For most of my youth, I existed in a maelstrom of self-doubt over my writing. I started at ten years old and knew, immediately, that I wanted to do it for the rest of my life. And I’ve always loved it. Those early years, I put no thought into the craft of it, no thought of story structure, of sentence construction, of theme, of arcs. I especially put no thought into an audience. Writing stories was just something I loved doing, and I did it with a complete lack of self-consciousness.

I don’t know when that changed, but I think anyone who engages in creative endeavors can relate. Eventually, no matter how much you love creating your art, you begin to look at the finished products with a more critical eye. Outside influences pollute the clear source of that creativity. This happens as you get better at it, too: you start to look back at older work, and it makes you cringe. That’s how you know you’re improving, how you know you’ve grown.

For me, a lot started to change when I discovered the authors who were writing the kinds of things I wanted to write. That was Stephen King, then Peter Straub, then onward from there. I studied, by way of reading and rereading, their techniques, their scenes, their sentences.

The more I began to study writing and storytelling as a craft, from as many sources as I could manage, the more I looked at my own work with a critical eye. My writing transformed. I was lucky enough that I’ve been writing long enough to have developed a voice on my own, and then to have that voice—and the craft surrounding it—shaped by study and practice. For years, though, I couldn’t speak about my own work with anything resembling confidence. The novels I finished, I set aside and rarely, if ever, let anyone read them.

Discovering how much I loved editing and revision was a major step in the right direction. I began to work on my finished drafts rather than simply setting them aside. Terrible rough drafts became readable—if still rough—second and third drafts. I began to engage with storytelling on a deeper, more cohesive level.

There’s a lot I can say about the work that goes into creating a polished final product, whether it’s a short story, or a novel, or even just a single scene. And it’s different for every individual writer, or any artist, no matter your medium. I can only speak from my personal experience.

My main point on that is: It’s possible to love your own work. More than merely possible, I think it’s worthwhile.

Toni Morrison said, “If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.”

I write what I want to read. It has become an inexpressibly joyful experience to learn how to love my own writing, my own books, after all the work that goes into them. This long course from crippling self-doubt and sometimes even hatred of my own work, into a sense of confidence in and love of my work, has been joyful and fulfilling, because at the end it means there’s a new book to read—and it’s one that, were it not written by me, I would want to read. I hope this doesn’t come off as egotistical or conceited. It’s something I hope any artist gets to experience: a love of one’s own creation.

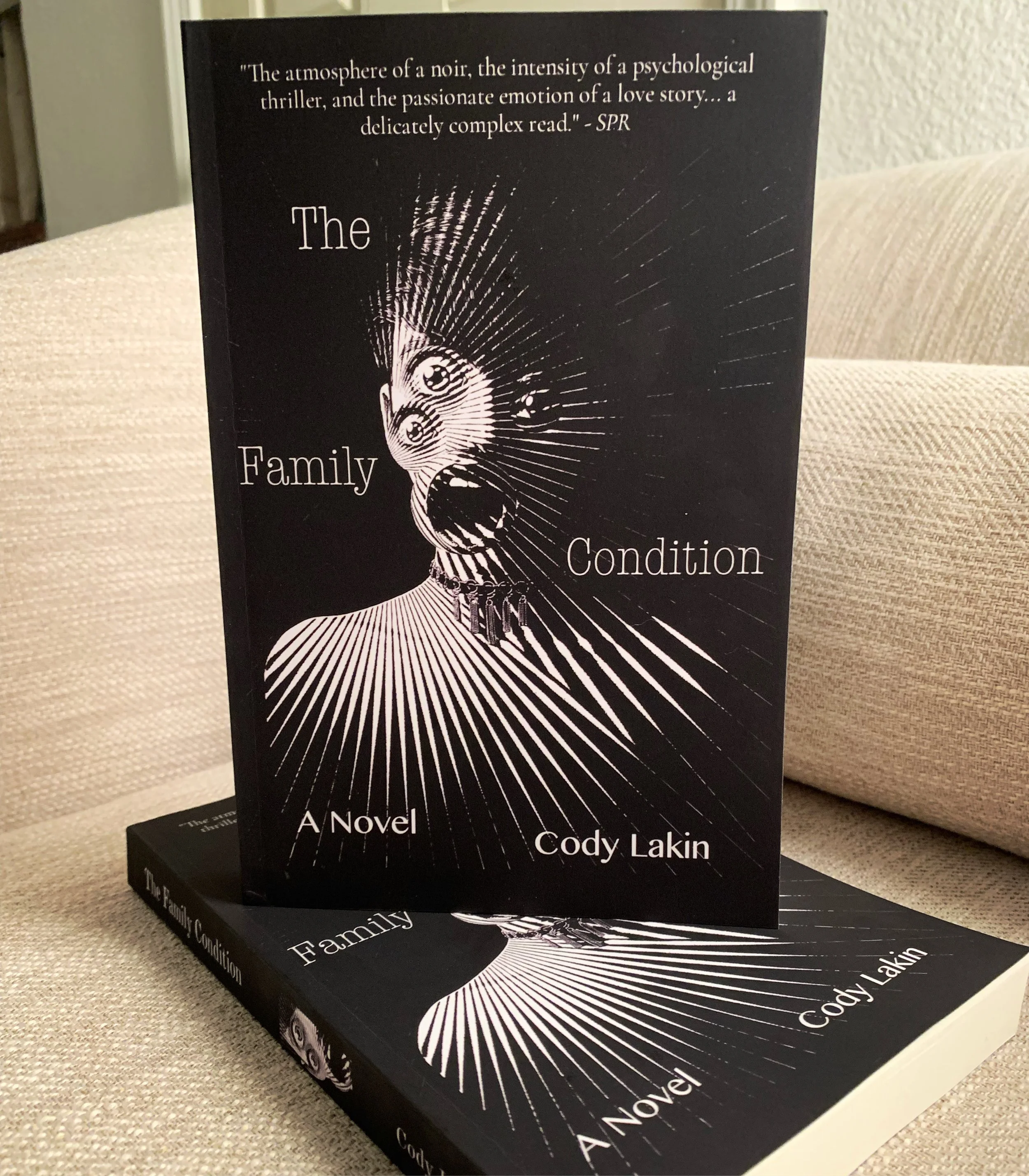

What I wanted to say about confidence is how my view of it has changed over the years. It’s easy to look at the finished product of an author, to hold a published, successful novel in your hands and to judge your own work heavily by comparison. That’s especially true in the rough draft stage, when you’re writing something and you feel like maybe it’s terrible, why do you even try, why keep going, when it sucks compared to the published novel in your hands. I don’t remember where I first heard this piece of advice, but in summary it’s simply this:

You can’t compare your rough draft to a final product that, itself, was once a messy rough draft. A polished final product went through months, if not years, of work to reach the stage it’s in. Rewrites, revisions, proofreads, copyediting. Not just from the author themselves, but also from professionals.

The rough draft is you telling yourself the story. You do what you need to get it out of your system and onto the paper. From there, once it’s done, you can work on it, shape it, polish it. With effort, with time, and—when it’s ready to share—with some help, too.

I’m confident as a writer now. But that doesn’t mean I put words down on the page and I’m confident in them. That means I’m confident in my ability to eventually create a product I’m confident in. I’m confident about my devotion to it, my willingness to work hard on it, until it’s where I want it to be. I still cringe at elements of my first drafts, and I probably always will. Honestly, I think that’s normal. But the self-doubt becomes useful; I use it as a tool to consider what to improve, rather than letting it overwhelm me into not writing for lack of confidence. I know I can take that messy, bad, possibly cringe-worthy rough draft, and eventually transform it into something I’m confident in.

“Confidence is preparation.” I heard it from Kobe Bryant, the basketball player. And sometimes I look at the work of the writers I most admire, and I wonder if they feel the same about their own writing, from first draft to final product. I have a feeling many of them do.