This post is somewhat difficult to write. I don't mean that in an emotional sense, or even in the sense of laying out and really articulating what I want to say about impostor syndrome. Talking about and understanding impostor syndrome has become surprisingly easy in the last couple of months since first realizing that I have it and have had it for most of my life. The hard part is, of course--and somewhat ironically, I'm aware--even admitting that I have it.

Impostor syndrome is described most often as a psychological phenomenon which manifests as a pervading feeling of severe, sometimes crippling doubt in an individual. Also sometimes merely referred to as the "impostor phenomenon," it tends to affect those who have achieved some kind of success, or who have made worthwhile accomplishments. It also affects young people on the precipice of, say, graduation, with responsibilities and grand new careers stretching out before them. It isn't merely doubt that it causes, however; impostor syndrome is the unique fear that your successes and accomplishments are not the result of skill, persistence, or hard work, but rather are the results of pure luck. Along with this is the feeling of being a fraud, the fear that people will one day recognize that you are a fraud and call you out for it.

You could say impostor syndrome is a clever and intellectual phenomenon on its own, because it comes with its own insurance, its own ability to perpetuate and validate itself while invalidating those who suffer from it: not only do you fear you are a fraud, but you are just as afraid of being discovered, of being found out, so you suffer in silence.

The irony that makes this post difficult to write is that part of me still doubts I have impostor syndrome. It's a voice in my head (not a literal voice, of course, more of a feeling) that forces me to ask "Do I have impostor syndrome? Do I really?" It then goes on, sounding very much like myself to me, saying "How narcissistic of you to think you have impostor syndrome. Clearly you're imagining it, and here you are writing a blog post about it as if you have any right to talk about it. As if your 'accomplishments' are serious enough to even warrant feeling like a fraud." And even as I write this out, forcing myself to be honest both with myself and in this post, part of me thinks I should just delete what I've written about it so far and forget it. The Impostor in me, as I have come to call that nagging voice, seems to speak in my own voice, and it's very good at sounding rational, it's very good at making me judge myself negatively.

I first discovered impostor syndrome no more than a couple of months ago. I saw it referred to in a post made by a writer on Instagram. It was a small post, more of a meme actually, but it was about how they always wanted to encourage writers who suffered from impostor syndrome, how they wanted always to validate them and tell them to persist and keep going. That context was enough to make me curious. I had never heard the phrase "impostor syndrome" before, strangely. But the simple act of googling it, which then led to watching a number of TED talks and reading psychology articles and studies about it, led to the realization that I do have impostor syndrome no matter how The Impostor (as I'll refer to that part of me in this post hereafter) continues to make me doubt that I do. And it's easy to see, when I look back across my life, how this phenomenon has affected and even shaped me.

For one, I have long realized that I am an existentialist. That in itself is a long story, suffice to say my discovery of the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, and of other existentialists, was a big deal to me in my later adolescent years. It wasn't so much that I identified with existentialism, but that in discovering existentialism as a school of thought, I understood I had always been an existentialist by nature. I have never been someone who doesn't question everything. Over the years, my mind has become quite good at deconstructing things, especially ideas, and filtering them through my avenues of understanding. This unconscious ability to deconstruct is probably related to a deep-seated curiosity that is a natural part of who I am--a curiosity about myself and the world--and I am continually, perpetually grateful for it. But there is a dark side to it. And for the most part, that dark side takes the form of The Impostor.

The more I come to understand my own impostor syndrome, the more I see how good it is at deconstructing. What is it deconstructing? It's deconstructing me. No one knows us better than ourselves, after all.

There was a time when I found myself asking, "Am I a writer? Am I really a writer?" And I'm sure to anyone reading this who knows me or has known me for a long time, the answer is fairly obvious. I think it's kind of funny now, actually, that this was ever something I struggled with. Since the moment I first started writing at age ten, there have been very few days, probably, that I haven't spent time writing. Even if it's minimal. But even so, The Impostor would ask and reason and deconstruct, saying "Are you really a writer, though? Clearly this is just something you're choosing to do. What right do you have to call yourself a writer? You aren't published. You aren't even that good compared to some of the books you read. Your writing style probably sucks, or is too simple, or too straight-forward, or too this, or too that. Stop pretending to be a writer." I never fully bought into those doubts when I was younger, but they were difficult to struggle with nonetheless. I have never suffered from serious writer's block--and sometimes I have doubts that writer's block truly exists as its own entity--but the few times I can say I may have suffered from it, I can look back now and see the role that The Impostor played. Impostor syndrome is said, by some psychologists and also by others who suffer from it, to be linked with anxiety and depression. My most crippling doubts about myself as a writer have been linked with the times in my life when I was also most depressed.

This particular doubt, however, is one I have been able to overcome in a number of ways. In his brilliant book for writers, The Modern Library Writer's Workshop, Stephen Koch offers a way of overcoming the question of whether or not you are a writer. In different words, of course, he suggested simply this: don't write. For artists in general, this translates to: try not making art. Try not doing the thing you have to do. There's no better way of realizing you have to do it. In fact, you'll probably end up making art about not being able to make art.

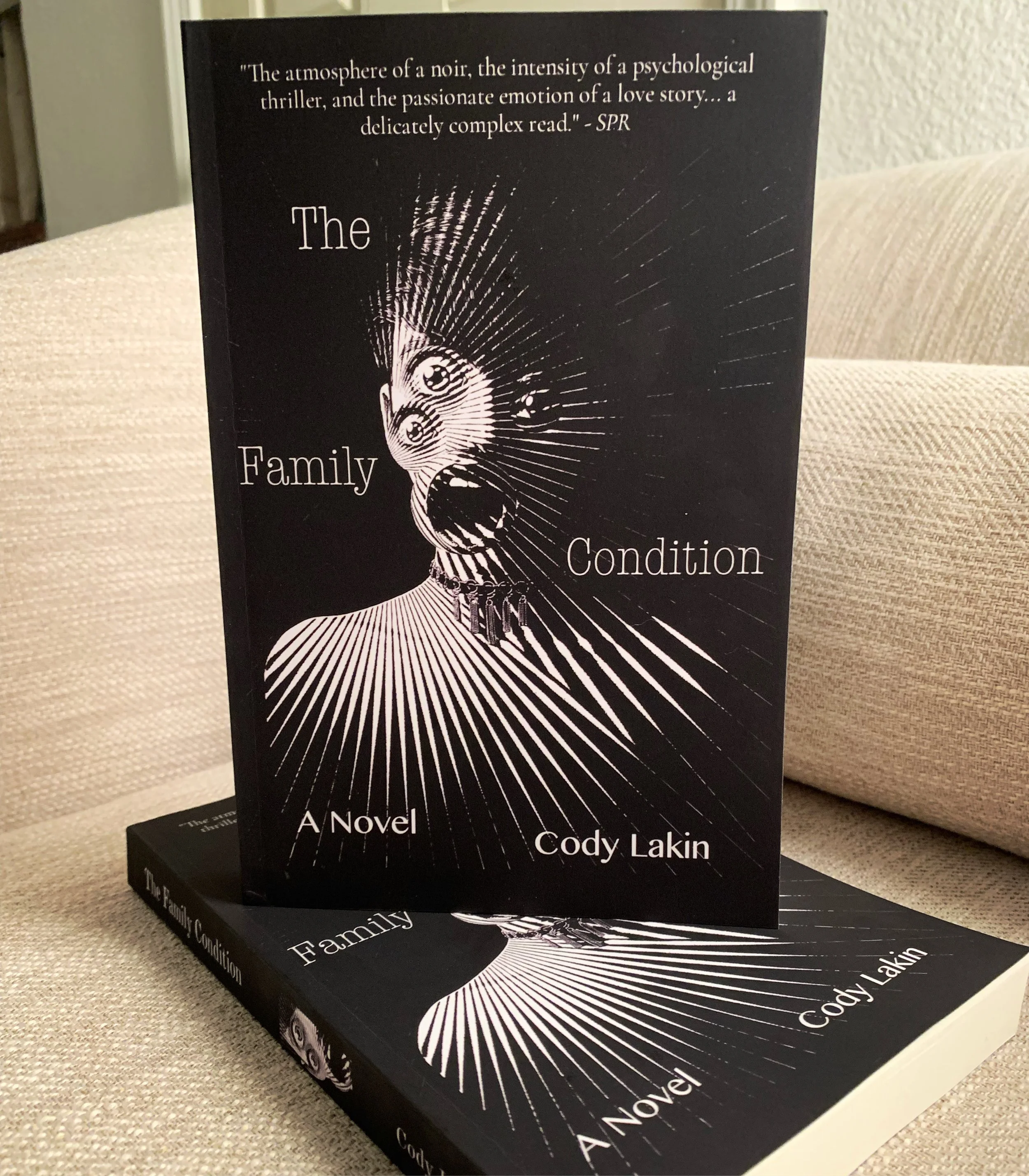

In 2016 I received a contract offer on what is now my first published novel, Other Endings. I remember how truly surreal it was reading that. I remember how the people around me, those I cared about, expressed their profound excitement--my parents actually crying, my girlfriend basically showering me with kisses and hugs--and how this excitement was beyond even my own. When I say it was difficult to believe, I genuinely mean it was, like, actually hard to believe. I became inexplicably concerned that the publisher would change their mind, realize my book wasn't so great after all--realize I was some kind of fraud, somehow, even though that doesn't even make sense--and revoke the contract offer.

When I've received negative reviews of my books, there is a unique contradiction in my own reaction. On one hand, I do have an ego when it comes to my writing because I know--or at least am pretty sure--that I'm a good writer. I cherish mixed and negative reviews just as much as positive reviews, because I think there is so much to learn from people's reactions to art--as long as it's a genuine and thoughtful reaction, and not just "It sucks!" or "It rocked!" And then there's The Impostor who reads those reviews and says "Oh look! Someone saw your book for what it really is." It's a strange contradiction and is kind of entertaining, because when I'm self-aware enough to combat The Impostor, which is more and more lately, I can use that negative deconstructive voice as a sort of representation of negative criticism. On one side there's the part of me that loves my own writing, loves my own stories, a part of me I've had to nurture over the years and am now able to embrace, and it's a wonderful and empowering feeling--I think every artist should learn to truly love their own art, to become interested in it as if it's someone else's. In other words, become a fanboy/fangirl of your own art. And on the other side of my mind there's the Impostor, telling me I'm a fraud, telling me that I'm not a writer, telling me I suck, telling me I don't have a right to be where I am.

You can learn to step outside of your mind, to see the different sides of yourself--in my case, the more Real Self, and the Impostor, in relation to my writing--and I can use them. Being your own worst critic can be incredibly useful, can be a form of self-discipline, when you don't buy entirely into your inner critic and don't become a self-defeatist.

Where once my impostor syndrome made it almost impossible to accept compliments on my work, I now know how to step away from it and see things more objectively. I catch myself doing this even still. I'll read a positive review for my book Fairlane Road, for example--and there have been some amazing reviews so far--and even though it's wonderful and exciting to read them, part of me (that is, The Impostor) doesn't believe a word of those reviews, and says "How nice of them to pretend to have liked your book," or some variation of that. It's the same with compliments from readers, and I have received many heartwarming words directly from people who have read my book and told me amazing things they felt while reading it. And part of me still takes their words from a strange distance, as if they're talking about somebody else. As if I'm an impostor in my own life, right?

And when I'm asked what it's like to be a published author, I will often say that it's surreal, and I truly mean it. It's surreal in the sense that I don't feel I belong here, that somehow I don't deserve my own accomplishments or successes, that I especially don't deserve to give myself credit for them or to let myself be happy for myself. Weird, isn't it? Or maybe not? I honestly don't know.

Now, this is the part where I get a bit mushy and close to emotional. I'll be brief.

Part of my experience with impostor syndrome hasn't just been the fear of being "found out," of being "outed as a fraud," of others seeing myself the way impostor syndrome has so often made me see myself: as inadequate, as not being enough, as undeserving, as ungrateful, as presumptuous, as egotistical/egocentric.

And then I have these amazing friends, and these amazing family members, and my amazing girlfriend, who pull me back into a reality I wasn't quite aware of.

Not too long ago I was catching up with a friend of mine (if you're reading this, thats you, Chris) and allowing myself to really open up about these kinds of things, but on the positive side. I've been through a lot in the last two years or so, and have learned more about myself in this period of time than I ever have over the course of the rest of my life. I talked about this more in my "Dispelling the Cliché of the Tortured Artist" post, but the short of it is that I find more stillness in my life now--both inside and out--and more peace. More presence. More joy. More sense of self. Along with that has been more awareness and understanding of the Impostor, and awareness of a problem is the first step in overcoming it. And after explaining to my friend how for the first time in my life I've truly started to love my own writing, he said to me something to the tune of "Cody, do you have any idea how great it is to finally hear you talk about your own writing like this?" And he went on to make me realize that I've probably never talked about my own writing in such an embracingly positive way. I don't have enough objectivity just yet, or enough clear memories since I've yet to delve into them, of how I used to talk about my own writing, but hearing that from my friend was sort of eye-opening, and deeply heart-warming. Rather than call me out for being somehow narcissistic or of patting myself on the back too much or of talking about myself too much (all of which were background Impostor-related fears during this conversation, and others like it), it made him genuinely happy to hear me talk about myself and my own writing like that. Where I've had friends who have said things to have increased my self-doubt in the past, or expressed things in such a way as to make me cautious of the things I share with them in regards to these kinds of things--and that, too, is fine, since there are all different kinds of friendships in our lives--this friend did none of that. He was simply a real and true friend, like he's always been.

Also not too long ago, I opened up to my parents about these insecurities, as I called them, and their reactions warm my heart even now to remember. For one, they couldn't believe I had insecurities at all. My dad looked at me and said "Cody, do you have any idea the things we say about you when we talk about you?" And went on to tell me. And my Mom got on me every time I subtly deflected a compliment, making sure I simply accepted those compliments without any quietly deflective modifiers.

And my girlfriend has made me feel so safe, is the word I used when I told her this, and so cared for, so that nothing but self-love and care will do. And she certainly wouldn't have it if I tried to chalk up my being a published author to just good luck.

In this way, my gratitude, my warmth, my love for those friends, for my family, for my loving and supportive girlfriend, for all of those who have been there for me in some form and supported me in my life--and in this context, as a writer--is immeasurable.

A lot of what it means to begin overcoming this kind of thing--impostor syndrome or anything like it--comes down to responsibility. Responsibility for your own life, for your own suffering, for your own failures, for your own successes and accomplishments. As Alan Watts once said, "Cheer up. You can't blame anyone else for the world you're living in." And when I say responsibility, I mean to take responsibility impartially, without self-judgment, without narcissism, without fear. It has taken me a long time to look at myself, to look at my own writing in this case, and come to a sort of peaceful and delightful and empowering realization: I'm a great writer, and I'm going to take responsibility for that. Not everyone would agree, of course--but what does that matter? That's the world we live in. If you suffer from these kinds of things, whether it's impostor syndrome or not--and I know everyone experiences doubt to some degree, and it can be about anything, not just art--learn to take responsibility for what you're good at, to realize your own skill and expertise, and if you're haunted by perfectionism, learn to accept what you aren't good at too, but do so without judging yourself for it. Start by stepping outside of your mind, realize you aren't your mind or your ego, and therefore you are not your doubt.

Most of all, open up. Don't suffer alone. As doctor and professor Jordan Peterson has said before, people need such little encouragement to truly blossom. There are people--friends, family, even strangers--who may surprise you with the wisdom and support and perspective they could offer. As much as the cynic in me used to think that maybe people really are islands, the truth is we aren't. A flower doesn't grow in isolation from a field. We don't exist in isolation from others, or from our environment. And it isn't all there to drag us down, it's there for us. We can be there for others just as they can be there for us.

And if you're an artist and you're reading this and you suffer from self-doubt or even impostor syndrome, I hope my sharing my experience has helped you, in some way. Sometimes even just learning what another person experiences with something you may also experience can be helpful, or insightful, or even empowering.

And go out and create some great art, and love it. Why not love it? And share it! Share it with me, even. I have found that a community of aspiring artists willing to engage and to share what they create--which is really sharing parts of themselves--is one of the loveliest things.

I'm sure you spend a lot of time with your art, after all. I'm sure it's as unique and beautiful as you are.